Blood in the Time of COVID

Dr. Suchi Pandey ’99 has worked to collect plasma from recovered coronavirus patients and to help evaluate it as a potential treatment.By: Meghan Kita Thursday, November 12, 2020 08:47 AM

Dr. Suchi Pandey ’99 stands in front of Stanford Blood Center, where she serves as chief medical officer. Photos courtesy of Ross Coyle/Stanford Blood Center

Dr. Suchi Pandey ’99 stands in front of Stanford Blood Center, where she serves as chief medical officer. Photos courtesy of Ross Coyle/Stanford Blood CenterIn her role as chief medical officer for Stanford Blood Center in California, Dr. Suchi Pandey ’99 must ensure that the blood the Center collects is safe for transfusion patients to receive. When COVID-19 first emerged early this year, her first concern was, “Could this novel coronavirus be bloodborne?” (Fortunately, there has been no evidence that COVID-19 can be transmitted through transfusion.) Her next concern was ensuring the safety of donors and staff at a time when personal protective equipment shortages were making headlines. Then, she quickly took on the responsibility of building the Center’s convalescent plasma program.

“Early on, it was determined that a potential investigational treatment could be convalescent plasma [collected from patients who’ve recovered from COVID-19]. It has been used in other respiratory illnesses, but there’s never been a very strong clinical trial,” says Pandey, who was a biology major at Muhlenberg. “The concept makes sense: If you take plasma from somebody with high levels of antibodies against the virus and give it to someone who’s currently ill, those antibodies can help in fighting the virus.”

Pandey, who’s also a clinical associate professor of pathology at Stanford University, received her first request for convalescent plasma from a California hospital on April 5, and on April 7, Stanford Blood Center conducted its first collection.

“We were one of the first programs in the country to bring up our convalescent plasma program,” she says. “It was a tremendous amount of work to set up procedures, train the staff and get everything ready.”

Pandey examines a unit of platelets in plasma in the lab.

In the spring and summer, Pandey also worked directly with COVID-19 patients at Stanford Hospital receiving convalescent plasma as part of a national expanded access protocol run by the Mayo Clinic to gauge the experimental treatment’s safety. That protocol ended August 23, when the FDA granted convalescent plasma an emergency-use authorization—the Mayo Clinic’s program produced enough data (via the 106,000 patients nationwide it enrolled) for the FDA to determine the treatment was not harmful.

“It was really interesting to be involved in the protocol on the hospital side: talking about it with patients who consented to it and tracking how they did,” Pandey says. But, she points out, it’s clinical trials—which have a group of patients receiving convalescent plasma treatment and another group receiving a placebo—that will actually tell the medical community if the treatment is effective.

Several clinical trials are ongoing. Stanford is leading one comparing the treatment against a placebo in COVID-19 patients who visit the emergency room but are not sick enough to be admitted to the hospital. Another large, multi-site clinical trial is evaluating convalescent plasma treatment in patients who are hospitalized but not intubated. Another trial, coordinated by Johns Hopkins, is examining convalescent plasma as a preventative treatment for people who aren’t currently sick but who’ve had a high-risk exposure to a COVID-positive individual.

“We don’t have data from any of these yet. They’re still enrolling patients. But these trials are needed to tell us if convalescent plasma works in these different settings,” Pandey says.

Between the clinical trials, the FDA’s emergency-use authorization and the rise in COVID-19 cases, national demand for convalescent plasma is increasing. Pandey continues to work to collect it while simultaneously ensuring the Blood Center has adequate reserves of blood for the hospitals it serves—no small feat in an era when many of the schools and workplaces that would ordinarily hold blood drives are operating remotely due to the pandemic.

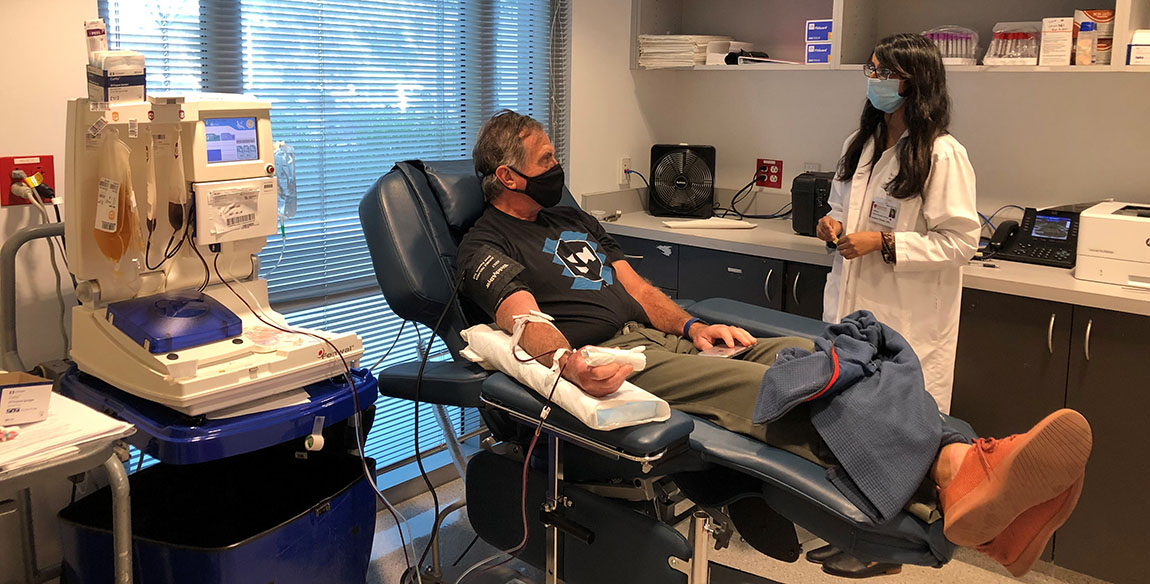

Pandey talks with a convalescent plasma donor.

Pandey is grateful for the California Department of Public Health’s (CDPH) partnership with blood centers to increase convalescent plasma collections in the state. CDPH sends letters to each positive patient in its database, making them aware that once they’re fully recovered, they can consider donating their plasma to potentially help others. That letter also serves as proof that the prospective donor had a positive test, which helps blood banks like Pandey’s be sure that they’ll be able to collect convalescent plasma from the donor.

“Any blood donor is incredible. They’re giving their time to donate their blood to help someone else,” Pandey says. “What makes this unique is there are not a lot of scenarios where someone who is recovered from an illness can give a product that can help someone who is currently sick with that same illness. We have donors who have come back six or seven times to donate their plasma.”