Sam Calagione ’92, the CEO and founder of America’s 12th largest craft brewery, Dogfish Head in Delaware, left Allentown with a bachelor’s degree in English and a dream of authoring the next great American novel. He moved to New York City to take creative-writing classes at Columbia University. There, he worked at a Mexican restaurant with a silly name (Nacho Mama’s Burritos) and a serious beer list (Chimay Red, Sierra Nevada Bigfoot, Anchor Liberty). He fell in love with craft beer and decided to try brewing his own—an experience that so delighted him and the friends who shared the finished product that he changed course and drafted a business plan to open Delaware’s first brewpub. He’s since grown the company dramatically, written or co-written five books about beer or entrepreneurship and won the 2017 James Beard Award for Outstanding Wine, Beer or Spirits Professional.

But before all that, he attended a boarding high school in his home state of Massachusetts called Northfield Mount Hermon. That’s where he met his wife, Mariah, who co-founded Dogfish Head with him, and where they sent their son and daughter.

At their son’s high-school graduation this spring, Mariah, a Northfield Mount Hermon trustee, presented him with his diploma. She texted her husband from the stage that the headmaster wanted the whole family to take a photo afterward in a room inside the school. When Calagione arrived, he found multiple photographers, the school historian and a diploma with his name on it.

“So, I technically graduated high school the same year as my son,” Calagione says, “but he wouldn’t let me go on the party circuit with him.”

Calagione was asked to leave the school in March of his senior year, after breaking the rules one too many times. The offense that sealed his fate was—foreshadowing—selling beer to his classmates, whatever he could convince an of-age stranger to buy for him.

“I’d already been accepted at some schools, and a couple of them revoked their acceptance,” Calagione says. “Muhlenberg was one of a few that was like, ‘Well, you’re an idiot, but we’ll give you a second chance.’ I really loved the visit I had to Muhlenberg: the stone buildings, the red doors and the green spaces. I just fell in love with the campus.”

You can see some of what Calagione loved about Muhlenberg reflected in the campus of Dogfish Head’s brewery in the rural town of Milton, Delaware. Between the main building—home to a tasting room, a kitchen, four brewing systems, two distilling systems and the corporate offices—and the canning and bottling facility, there’s a green space with a pond that hosts snapping turtles and herons. (Kim Koot, the Dogfish Head “experience ambassador,” says Calagione wanted to run a zip line between the two facilities but that legal advised against it.)

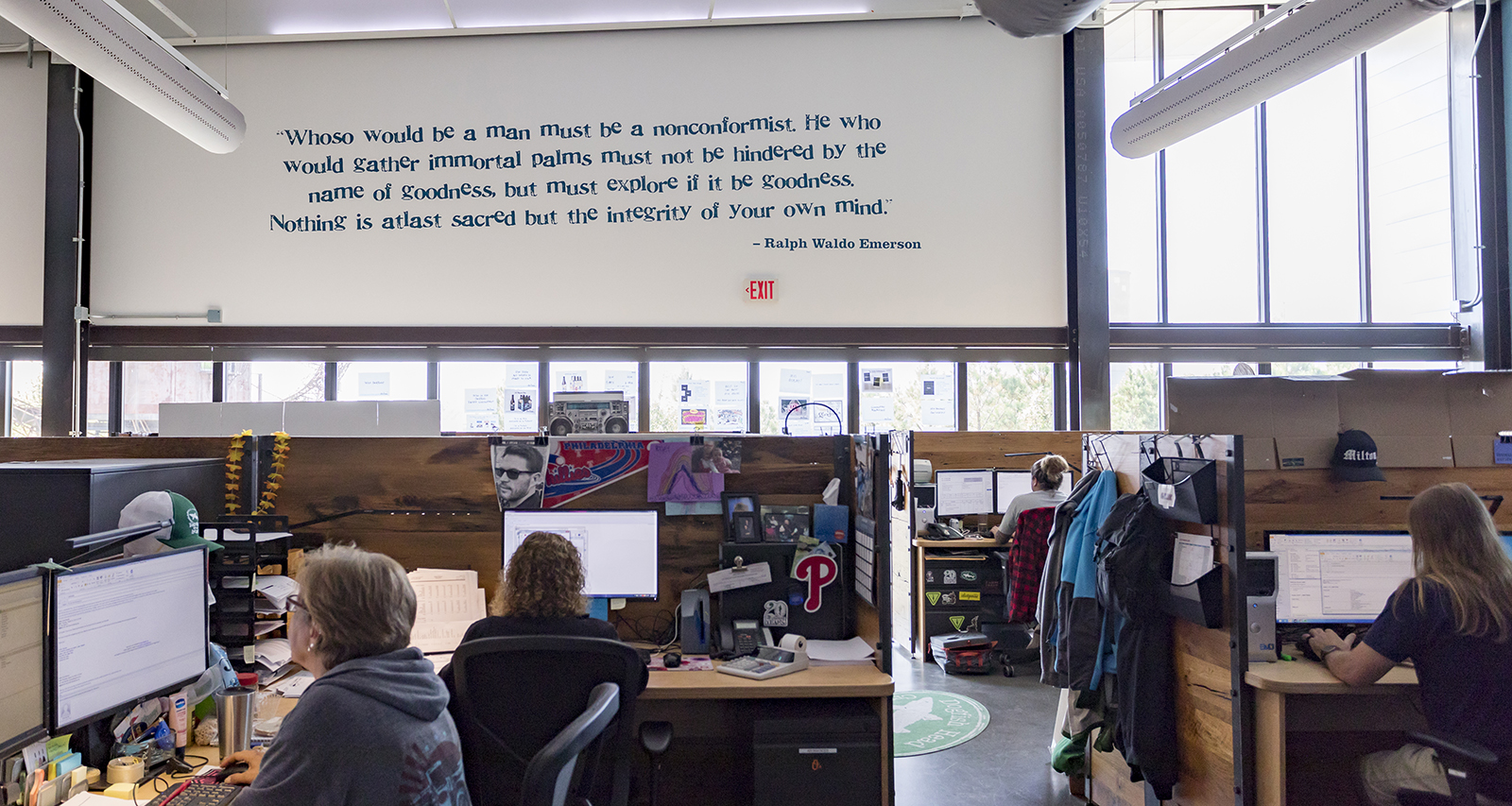

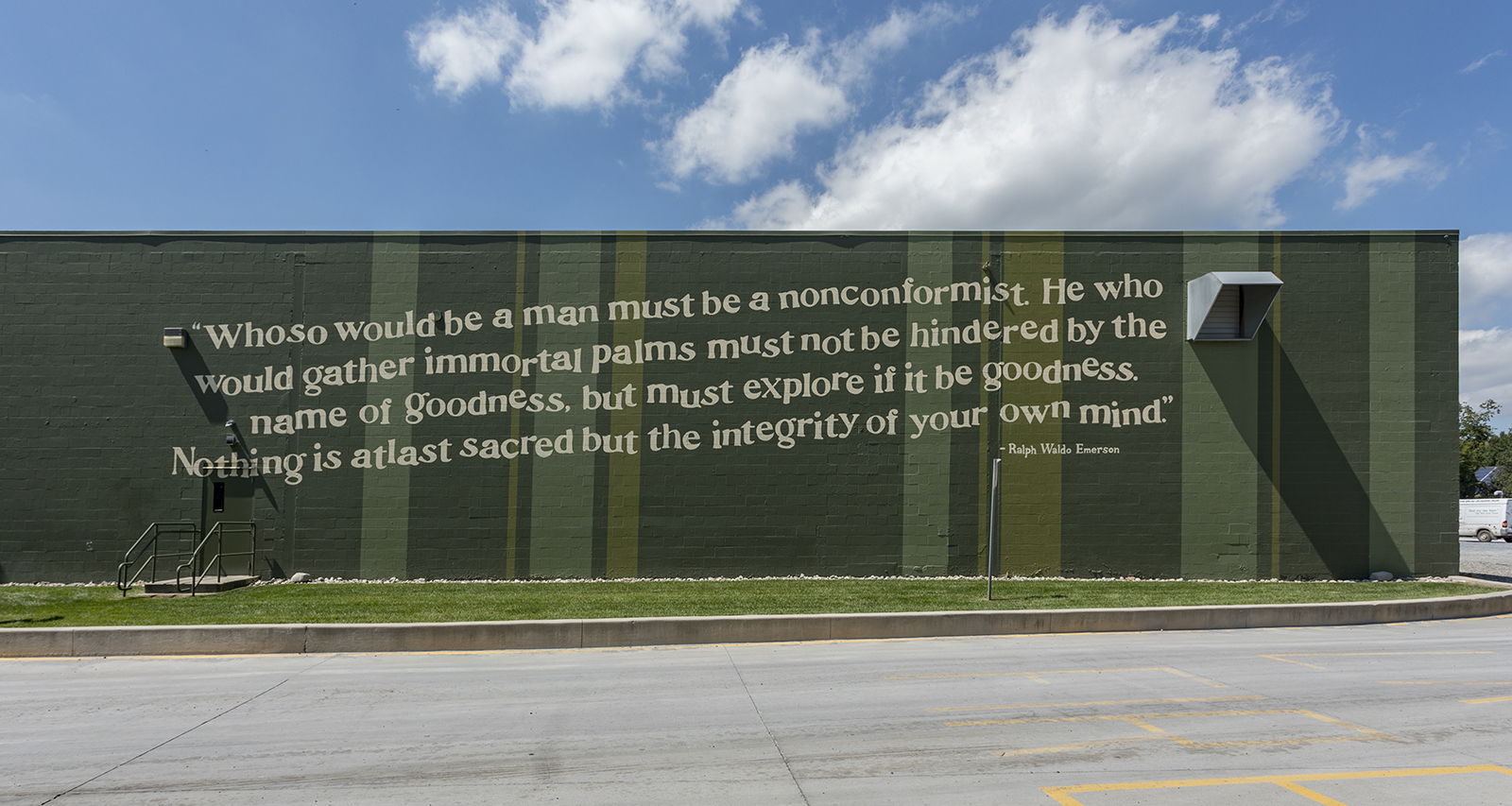

And you can see hints that an English major might be in charge throughout the Dogfish Head empire. At the company’s eponymous inn in nearby Lewes, books of poetry sit on the coffee tables in each room, and the lobby offers a lending library of 50 “American classics of literature” (including, for extremely motivated guests, David Foster Wallace’s 1,079-page Infinite Jest). And painted in several locations—inside the recently overhauled brewpub in Rehoboth Beach, above the office workers’ wooden cubicles and in enormous letters on the eastern facade of the main building—is the Ralph Waldo Emerson quote that appeared in Calagione’s original business plan as the company’s mission statement:

Whoso would be a man must be a nonconformist. He who would gather immortal palms must not be hindered by the name of goodness, but must explore it if it be goodness. Nothing is at last sacred but the integrity of your own mind.

“If you read quotes like that in context, Emerson does argue for the necessity of not just being a nonconformist but being a provocateur and disruptor,” says Jim Bloom, an English professor who had Calagione as an advisee. “Sam got as much out of his education going against the grain as he did going with it. That’s the ideal kind of student: who makes the most of it but also has some doubts.”

Brewing Ahead of the Curve

Calagione built the Dogfish Head empire—a brewery that’s forecasted to produce nearly 300,000 barrels distributed in 43 states this year, plus two distilleries, two restaurants and the aforementioned inn—on being a disruptor. When Dogfish Head opened as a brewpub in Mariah’s hometown of Rehoboth Beach in 1995, it was Delaware’s first brewery...because breweries were illegal in the state. Calagione successfully lobbied legislators to change the laws just weeks before the planned grand opening.

He’d been to his first brewpub while abroad in Australia his junior year—he says he was the first Muhlenberg student to study there—and the business model seemed like a logical starting place. The 10-gallon brewing system he installed in the original brewpub made Dogfish Head the smallest commercial brewery in the country.

“It was really homebrewing equipment that I MacGyvered into something a little more production-friendly,” Calagione says. Its limited capacity meant he was brewing two or three times per day, which was inefficient but allowed for experimentation true to the company motto of “off-centered ales for off-centered people.” And the kind of experimentation he had in mind was what set Dogfish Head apart from the 600 other American breweries that existed then: using culinary ingredients (like black limes, pictured) in the brewing process.

At the time, this was sacrilege: Calagione remembers presenting Aprihop, an apricot-infused India Pale Ale (IPA), at an industry dinner in 1997. The brewer who went next began his talk by saying, “I believe fruit belongs in your salad, not in your IPA,” which drew applause and laughter from the crowd.

“I went home with my tail between my legs,” Calagione says, “but we kept brewing fruit IPAs, and now look: There are thousands of breweries across America brewing fruit IPAs.”

It’s true that the marketplace has become far more crowded since the mid-’90s—there are more than 7,000 American breweries now, with two new ones opening each day. (Drive 20 minutes from the Dogfish Inn to its brewpub and you’ll pass at least two small competitors’ tasting rooms along the way.) But Dogfish Head has stayed relevant because it continues to innovate.

Take, for example, continual hopping: Most brewers add hops at the beginning of the boiling process and again at the end. After seeing a cooking show in which a chef peppered soup a little at a time as it simmered, Calagione applied the technique to brewing. For the test batch, Calagione rigged a vibrating tabletop football game to gradually shake hop pellets into the vessel below. The experiment proved successful enough to produce at scale, and in 2001, Dogfish Head released its 90-Minute IPA (so named for the amount of time it’s continually hopped), a beer praised for its intense hop flavor without the typically accompanying intense bitterness. Two years later came the less-boozy 60-Minute IPA, which continues to be the company’s top seller. Today, 60-Minute is brewed in Dogfish Head’s largest brewhouse (pictured)—a 200-barrel facility—using a pneumatic cannon that shoots hops into the boil every 60 seconds.

And that—the tale of how Dogfish Head’s bestseller came to be—is another example of what sets the company apart in a crowded marketplace: expert storytelling. Bloom remembers when Calagione returned to campus to speak to business students: “He said, ‘What you need to succeed in the kind of business I do is storytelling.’ He was already a talented storyteller before he got here, but that seems to be what he learned here.”

Calagione realized he fell short of being a world-class writer as he took creative-writing classes at Columbia: “But instead of getting dejected and disenfranchised, I thought, ‘Maybe I can make creative beer recipes that are my versions of poems or short stories and tell them through marketing.’” Each of the 21 beers on Dogfish Head’s 2018 release calendar has a story behind it. (Koot can talk at length about the saga behind the 10,000-gallon barrels made from Paraguayan Palo Santo wood in which the Palo Santo Marron brown ale is aged. It involves a man using a .38-caliber gun to attempt to fell the trees, which are so hard that they’re virtually bulletproof.)

And while some of those stories involve only folks within Dogfish Head, many involve outside collaborators. For example, the Midas Touch Ancient Ale was created with help from biomolecular archaeologist Patrick McGovern and based on residue found on drinking vessels inside King Midas’s tomb. The Pennsylvania Tuxedo pale ale was brewed in partnership with the Woolrich clothing company, after Calagione read that the company’s founder homebrewed beer using Pennsylvania spruce tips. Dogfish Head’s fast-growing SeaQuench Ale, a session sour, was created to complement the offerings at Chesapeake & Maine, the seafood restaurant Dogfish Head opened in 2016, and was brewed in collaboration with the National Aquarium.

“Evocative, well-differentiated stories in the marketplace, when done well, can allow you to charge a premium for something that’s recognized as having superior value,” Calagione says. “The story’s only as good as the tangible product itself, so it has to start with the distinction of the liquid, or the dish that we make in our kitchen, or the event idea that we build, and then the storytelling has to complement it.”

Building an Off-Centered Workplace

At first, Calagione felt more comfortable as a storyteller than as a businessman, but he knew he needed to hire people to help him make Dogfish Head a reality: “I felt a little weird about that. Like, I’ve been rebelling against The Man since I was a teenager, but now I’m talking about being The Man and running a company?”

One of the most significant hires he made happened within the first year or two: a professionally-trained brewer. Calagione says that at Muhlenberg, “I reconfirmed what I knew from high school, that I suck at math and I suck at science,” and the ability to be scientific about brewing is what makes for quality and consistency from one batch to the next. Nowadays, Calagione tries to brew at least monthly on one of the company’s smaller systems, but his days are mostly consumed by meetings and emails. Still, he uses the Notes app in his phone to jot down ideas he has while paddleboarding or biking for ingredients and techniques he wants to try, and he recognizes the importance of collaboration: “We have to keep that balance between academically trained brewers and folks like me that come at it more from a creative side. Otherwise, the regimented approach that’s taught at brewing schools would curtail us from taking the off-centered risks that we do.”

Even though Calagione leads the approximately 375 people the company employs, he still tries to create an environment in which he is not The Man. “I’ve never once referred to anyone that I work with as ‘my employee,’” he says. “We’re all coworkers at Dogfish, and when we all work for Dogfish and when Dogfish is working well, then really Dogfish works for us.”

On the walls of the largest conference room at Dogfish Head are photos of every coworker, grouped by department, complete with names and titles. It helps Calagione learn who’s who in a company that’s growing faster than his memory can handle, and they watch over the room whenever the leadership team is in there discussing the company’s future.

“They’re looking at us as we’re making the decisions, saying, ‘My livelihood is reliant on the people at this table making really good decisions for Dogfish,’” Calagione says. “We’re proud of this opportunity to provide a community where all of these people make their livelihood.”

And the community is full of like-minded, off-centered people. To work at Dogfish Head, potential employees go through an interview process that ends with “Liquid Truth Serum,” an evening of imbibing in which “we see if they’re still someone we want to work with,” Calagione says. Once in, any employee can brew beer on the company’s 10-gallon setup—similar to the one in the original brewpub—and Dogfish Head will foot the bill for the ingredients.

Walking through the brewery, Calagione spots And a Bottle of Rum: A History of the New World in Ten Cocktails by Wayne Curtis on the desk of Tara Bowden, a Dogfish Head tour guide. It is, she says, the third book that she and a small group of coworkers are reading for their informal beverage book club.

“You know cocktail umbrellas? They were invented to keep shade on the ice,” she tells Calagione. “I thought that they were just for style.”

It is an exchange between colleagues, not between an employee and The Man. And it is an exchange between two like-minded people who could have just as easily met at Muhlenberg as at a brewing empire built by a Muhlenberg grad.

Calagione often stresses that the company is about more than just beer—its motto was updated a few years back to be “off-centered goodness for off-centered people.” Based on the collaborations it takes on and the events it supports, it’s clear that Calagione and his coworkers are equally passionate about art, music, fitness, food, history and so much more. As Calagione puts it, “we are creatively omnivorous and curious and always learning.” It sounds almost like the vibe at his alma mater—if the Tavern on Liberty were an academic building.