Celebrating the 500th Anniversary of the Reformation with Documents as Old as It Is

A new exhibit in Trexler Library’s Rare Books room traces the history of Lutheranism and Lutheran education from 1517 until today.By: Meghan Kita Monday, October 30, 2017 04:00 PM

Special collections and archives librarian Susan Falciani arranges a document in the “Opening Luther’s Door: Lutheran Education from Wittenberg to Allentown" exhibit. Photos by Paul Pearson.

Special collections and archives librarian Susan Falciani arranges a document in the “Opening Luther’s Door: Lutheran Education from Wittenberg to Allentown" exhibit. Photos by Paul Pearson.In the collection that’s currently in Trexler Library’s Rare Books Exhibit room, “Opening Luther’s Door: Lutheran Education from Wittenberg to Allentown,” Muhlenberg’s historic and continuing connection with the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America is on display. In one of the cases closest to the entrance, special collections and archives librarian Susan Falciani points out the “number one coolest thing” that’s here.

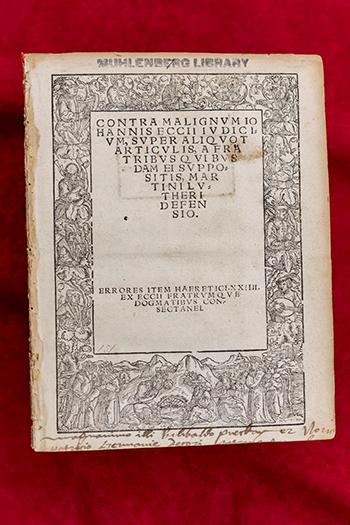

“This pamphlet (right) is supposedly signed by Martin Luther himself,” Falciani says. “I am 85 percent confident this is true.” Her confidence comes from the library’s research on who owned this document and when, but his signature isn’t the only reason it takes top billing.

“This pamphlet (right) is supposedly signed by Martin Luther himself,” Falciani says. “I am 85 percent confident this is true.” Her confidence comes from the library’s research on who owned this document and when, but his signature isn’t the only reason it takes top billing.

“The English translation of the title is basically ‘The Trial Against the Malignant John Eck,’” Falciani says. “This was one of Luther’s major feuds. They were firing pamphlets back and forth against one another,” arguing over religion (Eck was Catholic). This pamphlet series came after an in-person debate between the two men in the summer of 1519, a debate that resulted in a clearer picture of how Luther’s thinking diverged from that of the Catholic church.

“Printing was only 50 to 60 years old at this point,” Falciani adds. “Who knows if the Reformation could have even happened without it.”

The exhibit coincides with the 500th anniversary of the Reformation, which began when Luther posted his 95 Theses on October 31, 1517. While the exhibit contains documents from the Reformation’s early days, it also includes pieces from when Muhlenberg was founded as the Allentown Seminary in 1848. Falciani credits Peter Pettit, associate professor of religion studies and director of the Institute for Jewish-Christian Understanding, for helping provide context to the artifacts she assembled. The exhibit’s final portion, which chaplain Callista Isabelle helped put together, reflects what a Lutheran education means in a modern context.

“The church is not called to serve itself; it’s called to serve the world,” says Pettit. “In a Lutheran understanding of higher education, we’re not about training Lutherans or making Lutherans more prominent. We’re about serving the world, and that means in all the variety of the arts and sciences and trades and also across the diversity of human religious experience.”

The exhibit opens tomorrow, October 31, and is open through March 31, 2018. If you’re not able to see it in person, here are a few other highlights from the collection, courtesy of Falciani:

Martin Luther’s Sermon Preached at the Castle at Leipzig for the Day of St. Peter and St. Paul. Leipzig: Wolffga[n]g Stöckel, 1520. 8pp.

Martin Luther’s Sermon Preached at the Castle at Leipzig for the Day of St. Peter and St. Paul. Leipzig: Wolffga[n]g Stöckel, 1520. 8pp.

Luther delivered this sermon focusing on Matthew 16:13-19 on June 29, 1519, for the feast of St. Peter and St. Paul. It immediately precedes his debate with John Eck and deals with the relationship between the doctrine of justification and that of the church. It reflects Luther’s thinking on the role of the papacy as he prepared for the Leipzig Debate. The title page features a very early woodcut portrait (far left) of Luther.

Portrait of Martin Luther

“There are 28 years difference between that woodcut and this copper engraving (near left, 1548) by Melchior Lorck,” says Falciani.

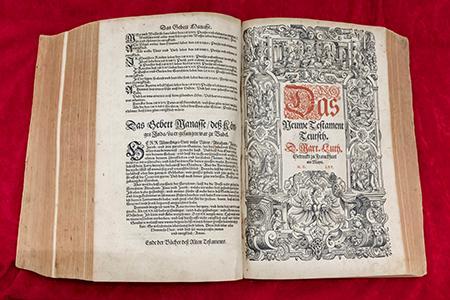

Luther’s German Bible (right)

Bible: that is the whole Holy Scripture in German. [Frankfurt: Georg Raben et al, 1565].

Luther translated the Bible into German from ancient Greek and Hebrew into Early New High German for the use of laypeople. He completed the New Testament in 1522, building upon the work done by Erasmus in his 1519 edition of a Greek New Testament. His reliance on the relatively new Renaissance scholarship of the ancient languages gave him access to versions of the Bible that he believed were largely unaffected by the church’s corrupting influence, transmitted through the Latin Vulgate. Without the development of the European universities and their classical curricula, Reformation theology could not have developed its foundational principle of “scripture alone” (sola scriptura) in the same way.

The first complete “Luther Bible” was published in 1534 by Hans Lufft of Wittenberg, and was a collaborative effort shared by Melanchthon, Caspar Cruezigar and others. Luther continued to revise the work until his death in 1546, when a revision was published. This 1565 edition is the earliest Luther translation that the library holds.

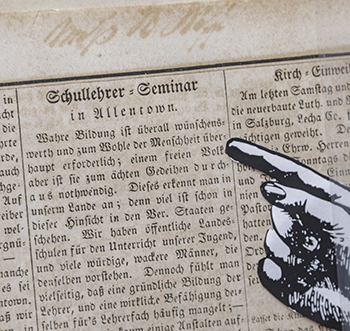

The Youth’s Friend, a Sheet for Families, School, and Church. Allentown, PA: S.K. Brobst, 1847-1857.

The Youth’s Friend, a Sheet for Families, School, and Church. Allentown, PA: S.K. Brobst, 1847-1857.

Rev. Samuel Kistler Brobst was one of the greatest motivating factors behind Lutheran education in the Allentown region, and he ultimately was the driving force behind the foundation of the Allentown Seminary, which ultimately became Muhlenberg College. His young German-language paper for Lutheran youth, Der Jugend Freund (left), announced in this October 1847 issue the establishment of the Seminary.