The Study of Play

Assistant Professor of Media & Communication Irene Chien helps students understand the prominent role of video games in the broader media landscape.By: Meghan Kita Monday, March 22, 2021 08:19 AM

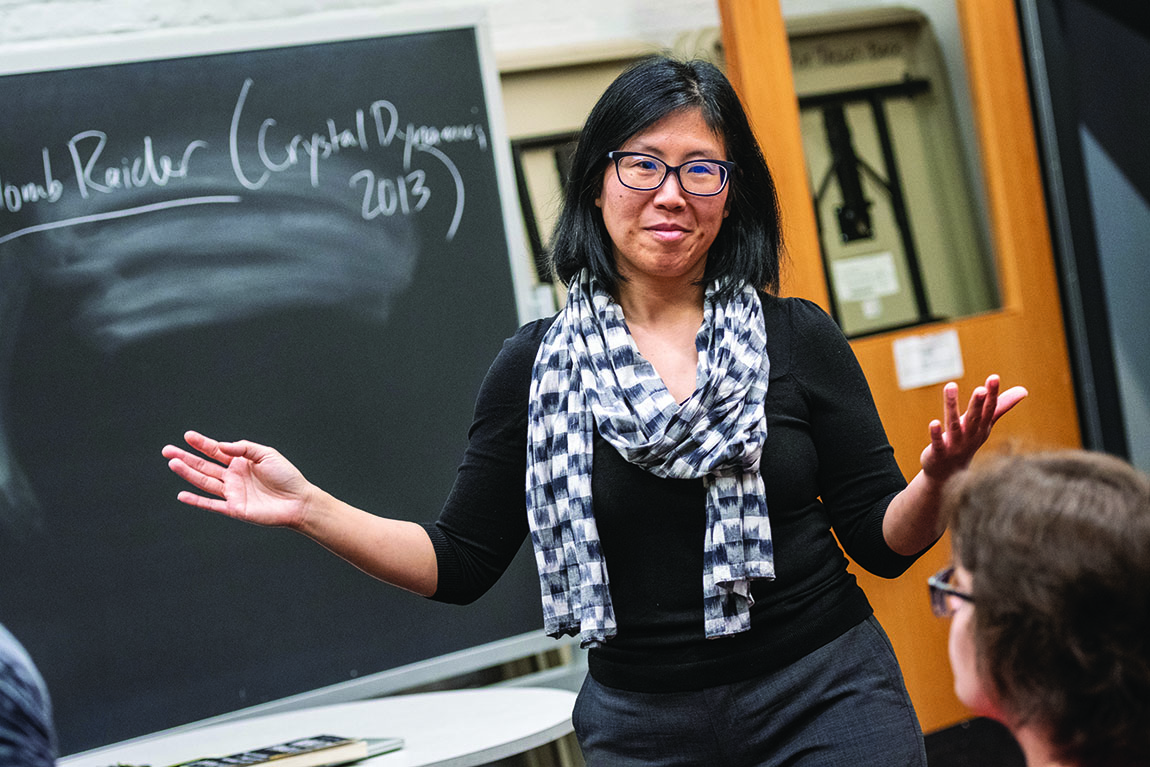

Assistant Professor of Media & Communication Irene Chien teaches Play and Interactive Media in Fall 2019. Photos by Ryan Hulvat

Assistant Professor of Media & Communication Irene Chien teaches Play and Interactive Media in Fall 2019. Photos by Ryan HulvatPlay and Interactive Media, an advanced seminar taught by Assistant Professor of Media & Communication Irene Chien, requires students to attend an hour-long lab session each week. In that lab, the classmates do something together that they might have otherwise been doing on their own in their residence halls: They play video games.

“I have to spend a lot of time helping students justify for their parents why they wouldn’t be wasting their time taking a class on video games,” says Chien, a digital media scholar whose primary focus is on games.

One key justification: Video games have out-profited Hollywood films—which have entire academic programs devoted to their study, including at Muhlenberg—for more than a decade. Even before the pandemic, the average person spent more time playing video games than at the movie theater. (Remember that games are more than just Fortnite and Call of Duty—Candy Crush, Words with Friends and Solitaire all count.) And because modern gameplay takes place online, players are constantly connected with both friends and with strangers in a way they weren’t in the era of arcades and Ataris.

“Video games are a site in which people make meaning in their lives,” says Chien, who tries to draw a mix of students (some who are interested in video games and some who aren’t) to her classes. “If we are to dismiss [games], we have to know what, exactly, we are dismissing. If we have committed full-on to them, we need to consider what is attractive and interesting about video games that is shaping how people think about themselves and society.”

Students in Chien’s Play and Interactive Media class react as they play a game during the course’s lab component in Fall 2019.

Chien became interested in studying video games after her younger brother, who was away at college, became so deeply immersed in the online role-playing game Dark Age of Camelot that he fell out of touch with his family. She saw firsthand how some players constructed their lives around games and wanted to better understand that universe.

For her dissertation at the University of California, Berkeley, Chien chose to focus on two genres—martial arts games and dance games—that highlight the actions of characters’ and/or players’ bodies. In martial arts games, it’s not about how many weapons a player can collect but how skillfully the player can move the character on the screen. (Chien, who also teaches Asian American Media, notes that martial arts games were the first to prominently feature Asian people.) Dance games, such as Dance Dance Revolution and Just Dance, invite spectators to watch the players themselves rather than watching the screen.

“Another really interesting thing about dance games is the way they have emerged at different points to train people into new technological interfaces,” Chien says. For example, one of the most popular games in the App Store when the iPhone debuted in 2007 was called Tap Tap Revenge, which had players swiping and tapping—novel movements at the time—to the beat.

“Music and dance are actually really programmed ... They’re codified movements and patterns and repetitions, but we experience them as being expressive and freeing,” Chien says, adding that the iPhone’s predecessors had been marketed as tools of productivity. “It was a really interesting trick Apple played to create a device with the functionality of a Blackberry but with this sense of breaking norms and expressing your true identity.”

Chien’s focus on dance and martial arts games in her research dovetails with how she teaches her classes, which entails “pushing back against this association of video games with a type of masculinity that is heavily policed and that keeps women, people of color and queer people out,” she says. One way she does this is by introducing her students to games whose primary goals for players are experimenting and taking risks rather than attaining power and mastery. She also tries to prioritize games students wouldn’t have encountered on their own, such as Katamari Damacy, originally produced for the PlayStation 2.

“You’re just a creature rolling a giant ball that becomes larger and larger as it sticks to all the things you pick up,” she says. “It’s disorienting and silly. Failing in the game is just as interesting and fun as winning in it.”

To support the lab components of her classes as well as students interested in doing independent research on video games, Chien began a collaboration with Digital Cultures Technologist Tony Dalton. In 2014, Dalton built a mobile video game lab—a cart that can now be used to play games designed for 16 different systems—and established a video game library that has accumulated nearly 100 donated titles.

The two hope to find a prominent place in Walson Hall to display the lab and library, Chien says, “in the hopes that it both makes the media-comm space more welcoming, because play is always an important way to enter into learning, and reminds us to take video games seriously as a mode through which we experience the world and a central part of media & communication studies.”