Perspective: Judicial Review

The Founding Fathers designed the Supreme Court to be apolitical. Will the Court’s current membership be able to uphold that appearance?By: Ross Dardani Wednesday, December 18, 2019 08:01 AM

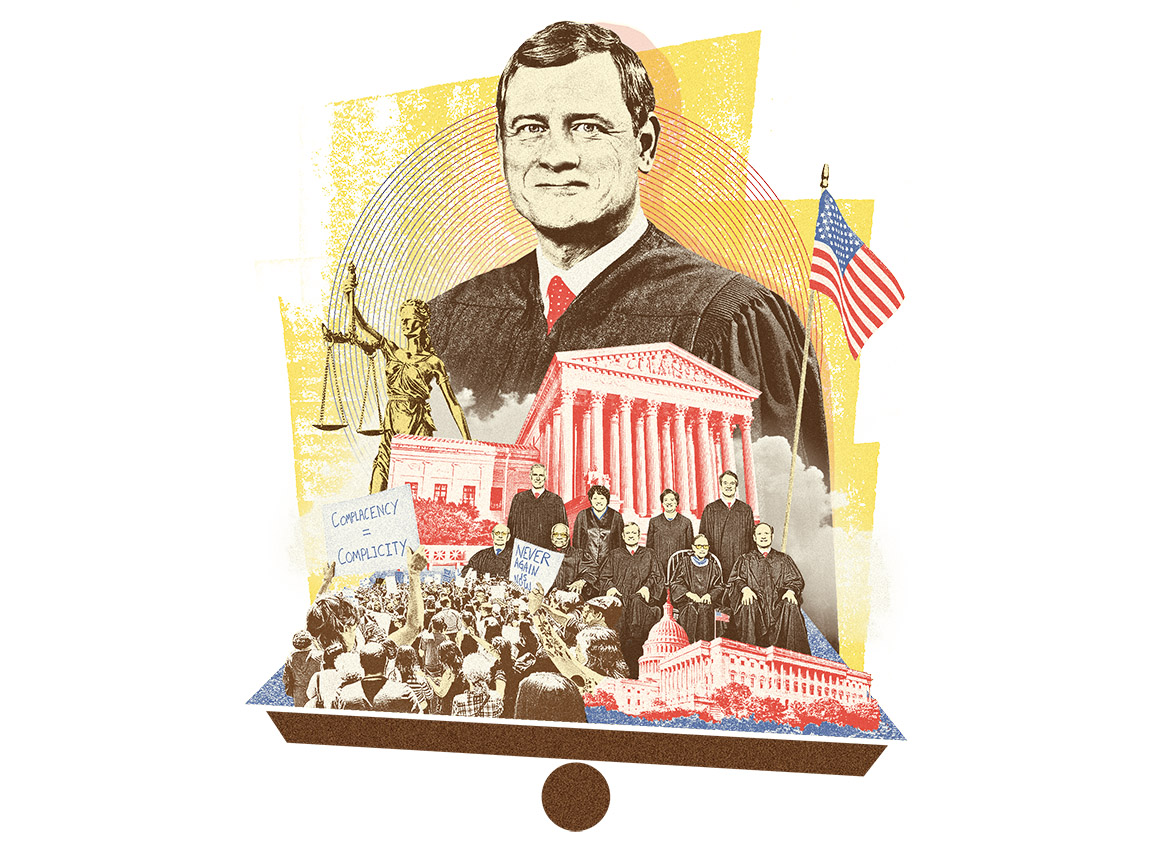

Illustration by Ryan Olbrysh.

Illustration by Ryan Olbrysh.Perspective is a feature of Muhlenberg Magazine where faculty, staff and alums share their expertise and experience on current issues and events. This article was originally published in the Fall 2019 issue of Muhlenberg Magazine.

Five Democratic senators recently filed an amicus brief in New York State Rifle and Pistol Association v. City of New York, for which the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in December. While the case, which concerns regulations on licensed gun owners in New York City, has generated media attention as the Court’s next potential landmark Second Amendment ruling, the brief has drawn coverage, too. “The Supreme Court is not well. And the people know it,” the Democratic senators warn. “Perhaps the Court can heal itself before the public demands it be ‘restructured in order to reduce the influence of politics.’”

The senators are referencing a new poll in which a majority of Americans agree that there is a need to alter the Court to make it less political. In response, Chief Justice John Roberts said that the justices “don’t go about our work in a political manner,” but “when you live in a politically polarized environment, people tend to see everything in those terms. That’s not how we at the Court function, and the results in our cases do not suggest otherwise.”

The Supreme Court’s legitimacy relies on the myth of judicial independence: the idea that justices are impervious to external—especially political—influences and reach decisions by impartially interpreting the Constitution. Alexander Hamilton, in Federalist #78, argued that the only way to insulate the judiciary from outside forces is by granting justices lifetime tenure. Not having to run for election would allow justices to ignore public opinion when they may be forced to strike down legislation that, while perhaps supported by most people, is unconstitutional. Hamilton believed that while the judiciary would be the least dangerous branch because it lacks the power of the sword (it cannot enforce its decisions) and the purse (Congress controls spending), it would have the power to persuade people of what is constitutionally permissible through rulings that depend solely on the justices’ dispassionate reasoning.

Of course, the Court has always been influenced by the political, cultural and economic forces shaping U.S. society. Its legitimacy depends on public support, yet the myth of judicial independence remains essential to the judiciary’s ability to exist as a coequal branch of government. But now, for the first time in the Court’s history, all five of the conservative justices have been nominated by Republican presidents and all four of the liberal justices have been nominated by Democratic presidents. What happens to the role of the judiciary when a conservative majority on a highly politicized Court coexists with an increasingly progressive U.S. populace?

There have been times in the Court’s history when it continued to issue rulings that were in opposition to a clear national majority. From the mid-1890s until 1937, the Court established a “right to contract” that it argued was implied in the Constitution, which allowed businesses to force laborers to work in inhumane, hazardous conditions, as long as employees were willing to agree to the terms set by their employer. Based on this implied right to contract, the Court, influenced by the dominant economic theory of the time, struck down legislation that attempted to regulate business, including laws that attempted to limit the number of hours an employee could work each day, workplace safety laws, minimum wage laws—Congress was even overruled from prohibiting child labor.

If the public is going to maintain faith in the independence of the judiciary, at least one of the justices that make up the current entrenched conservative majority is sometimes going to have to vote against their policy preferences.

The Court eventually began to allow for an increased level of federal intervention in the economy with a broader interpretation of the Commerce Clause. This shift was only after public opinion had clearly moved against the Court as the Great Depression continued and FDR threatened to pack the Court with justices supportive of his New Deal policies. The “switch in time that saved nine” demonstrates that when the Court has had moments of conflict against a broad national coalition and is perceived as not acting independently, it has issued decisions to align with the public mood in order to help preserve its legitimacy.

After the retirement of Anthony Kennedy and the confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh last year, Roberts became the swing vote in the most high-profile issues the Court faces. In its first term with this new lineup, the Court rebuked the Trump administration’s attempt to add a citizenship question to the census questionnaire. This suggests that Roberts, while a deeply conservative justice, is cognizant of the importance of maintaining an independent judiciary for the long-term health of the U.S. political system. But the Roberts Court’s refusal to settle disputes involving political gerrymandering, its broad deference to executive authority, its rulings in favor of big business and its increased willingness to overturn longstanding precedents hint at a future in which the Court’s legitimacy will be tested.

If the public is going to maintain faith in the independence of the judiciary, at least one of the justices that make up the current entrenched conservative majority is sometimes going to have to vote against their policy preferences. If not, there will continue to be threats to restructure the Court (e.g. court-packing, getting rid of lifetime tenure) by a broader range of people. These reforms would hasten the shift in public opinion toward viewing the Court as nothing more than a political institution and would diminish its power, prestige and influence in U.S. society. Roberts will find himself forced to balance his desire for a conservative majority on the Court to move the law incrementally but steadily rightward against his concern with preserving the Court’s legitimacy as an independent branch of government.

Ross Dardani is an assistant professor of political science at Muhlenberg College.