Students Probe Slime Molds' Memory During Summer Research in Neuroscience

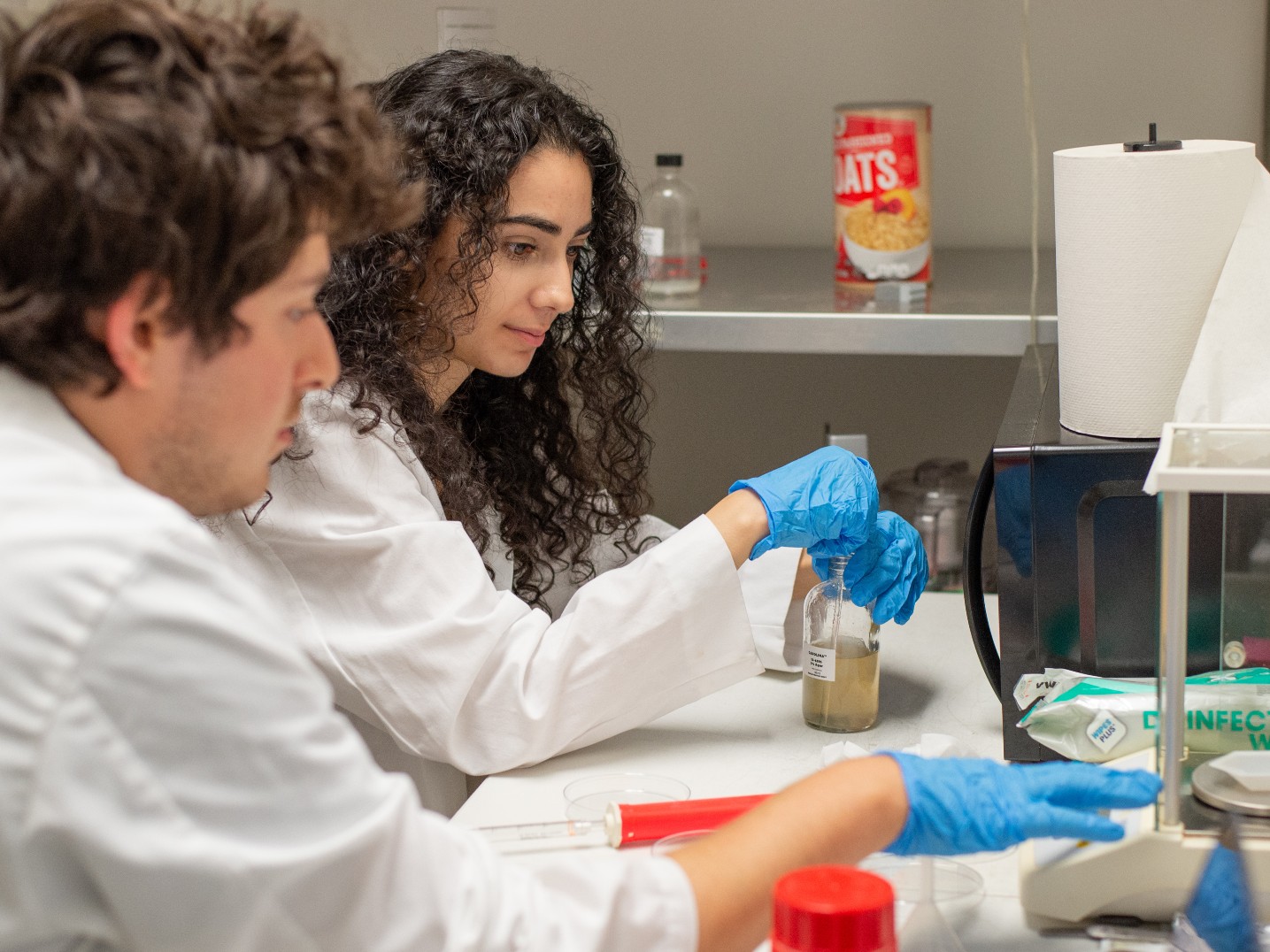

Liam Safran ’23 and Jenny Makhoul ’23 worked together to investigate the mechanisms of memory possessed by this unique single-celled organism.By: Sarah Wojcik Wednesday, September 7, 2022 09:36 AM

To see it — a thin, neon yellow splotch in a petri dish — you’d be forgiven for your lack of faith in the cognitive abilities of slime mold.

This humble, single-celled organism is neither plant nor animal nor fungus (though for many years it was categorized as such). Slime molds are members of a different biological kingdom: the Protistas.

This summer, Liam Safran ’23, a neuroscience major on the predental track, and Jenny Makhoul ’23, a biochemistry major, have been getting to know the organisms that are known for their ability to baffle researchers for decades.

“It’s kind of interesting because here’s this thing you never thought about your whole life, and now it’s like such a central part of my every day,” Safran said with a laugh. “Over time you do sort of develop a strange relationship.”

Working in the lab of Gretchen Gotthard, professor of psychology and neuroscience, Makhoul and Safran have been investigating how slime molds can create memories — and in what ways those can be interrupted — despite lacking a central nervous system.

Slime molds’ bodies, which consist of a single cell, can stretch, grow and move toward food sources. They will also avoid obstacles they detect as harmful. And through experimentation, Safran and Makhoul have collected data that appears to show that though slime molds can learn whether a perceived danger is real, that memory can be disrupted in such a way as to cause them to forget such information.

The lab partners coaxed slime mold to a food source the organisms found especially tasty — in this case some oats. In order to get to the oats, the slime mold had to cross a “bridge” covered in vinegar. They could tell the organisms had habituated to the vinegar when they found them crossing the bridge as quickly as those slime molds that didn’t have to contend with the vinegar.

This result shows that the slime mold had begun to demonstrate habituation, a non-associative form of memory. Safran and Makhoul are hoping to expand the experiment to explore whether the slime mold can perform more complex, associative memory functions that could be disrupted by an amnestic agent.

Part of what has been so rewarding about the research, Safran said, is that neuroscience faculty were so adamant that he tackle a research topic that resonated with him personally. Safran said he’s always been fascinated by memory and has become increasingly interested in exploring science that challenges the preconceived notions of mind and body separation.

Choosing to work with slime mold meant he and Makhoul had to do a lot of reading and research to prepare the lab for the organisms, but such work increased his sense of ownership in the science.

“I really enjoyed learning how to design and execute the research from every corner of it,” Safran said. “You just really become intimate with the scientific process. And you gain a lot of discipline from that.”

By taking on this particular research topic, Makhoul was stepping into a different field of study, one motivated by her passion for understanding memory and problem-solving. The result was digging into a subject of great interest and widening her base of knowledge.

“It has been rewarding being able to have the opportunity to branch out of biochemistry for a bit and focus on something I am typically not familiar with,” Makhoul said. “I was able to discover another science I am passionate about.”

The data being collected on the slime mold could have implications for further understanding of biological memory, Safran said, particularly concepts related to memory storage. The research shows that a brain is not required for the acquisition and modification of memories, Gotthard explained. Safran and Makhoul’s work has the potential to be the first published study to show memory reconsolidation is possible in an organism without a brain, Gotthard said.

"Research is a challenging undertaking even when researchers are continuing a line of established work. Beginning from scratch, the way Jenny and Liam and their earlier collaborators did, increases the challenge significantly," Gotthard said. "The persistence and creativity that Liam and Jenny put into this work made all the difference in moving this research forward."